At the end of Chapter 3 of Debunking Economics, Steve Keen has a fantastic section on a paper by Reihard Sippel called An Experiment on the Pure Theory on Consumer Behavior. This paper tests the theory of the “rational” consumer of in an experiment like setting.

Paul Samuelson defined consumer rationality using four basic principles:

1. Completeness: When given two combinations of goods A and B, a consumer can decide which one he prefers. So A > B, B > A, or A = B (he can get the same degree of satisfaction from both combinations, in which case he is indifferent).

2. Transitivity: If A is preferred to B, and B is preferred to C, then A is preferred to C.

3. Non-satiation: More is always preferred to less

4: Convexity: The marginal utility a consumer receives from each commodity falls with additional units consumed.

This definition is still widely used in Intro Economic classes (as well as some more advanced courses).

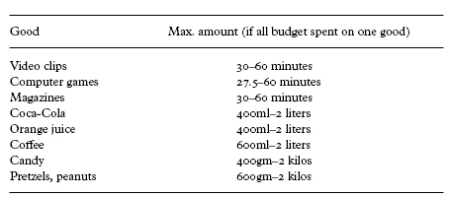

Sippel tested consumers to see if they acted according to these rules. He gave his test subjects a set of eight commodities to choose from, a budget, and a set of relative prices.

The experiment was repeated ten times, with ten different price and budget combinations designed to test various aspects of Revealed Preference. Since Sippel only wanted to analyze individual behavior, only one subject at a time came to the laboratory. There was also no time constraint placed on the subjects to make their choices. Basically, Sippel created ideal experimental conditions for consumers to meet the Axioms of Revealed Preference.

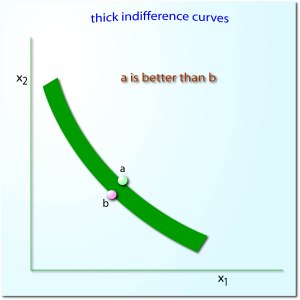

In Sippel’s first experiment, 11 out of 12 of the subject violated Samuelson’s criteria for a rational consumer (laid out above), and in the subsequent second experiment, 22 out 30 violated Samuelson’s criteria. Sippel tried to save the “rational consumer” by saying that consumers can’t distinguish the differences in utility between two bundles of goods.

It might be the case that the difference in ‘utility’ or satisfaction between a chosen bundle and another one revealed preferred to it is, in fact, hardly noticeable for the subject. We might then regard the inconsistency of not choosing the seemingly preferred bundle as being of minor importance.

Sippel controlled for this by essentially making the indifference curves thicker.

By doing this, the number of violation was greatly reduced, but it also had the impact of making random choice appear more rational than the consumption decisions of the subjects.

In other words : a non-parametric test of optimizing behavior with 95 % efficiency has practically no power against the alternative of purely random choice.

Sippel concluded his experiment with:

We conclude that the evidence for the utility maximization hypothesis is at best mixed. While there are subjects who appear to be optimizing, the majority of them do not. The high power of our test might explain why our conclusions differ from those of other studies where optimizing behavior was found to be an almost universal principle applying to humans and non-humans as well. In contrast to this, we would like to stress the diversity of individual behavior and call the universality of the maximizing principle into question.

Despite the fact that a few test subjects met the Axioms of Revealed Preference, most did not. Human decision making is a complex process that varies from individual to individual. When given a situation seemingly as simple as choosing various bundles of eight commodities in a controlled experiment, there is a number of underlying processes that occur in our brains. This makes simple outcomes such as “maximizing utility” extremely complex. Keen provides a useful analogy:

In Sippel’s experiment, however, this resulted in 8 raised to the power of 8 – or in longhand 8 by 8 by 8 by 8 by 8 by 8 by 8 by 8 by 8, which equals 16.7 million. Many of these 16.7 million combinations would be ruled out by the budget – the trolly containing a maximum amount of each items is clearly unattainable, as are many others. But even if the budget ruled out 99.9 percent of the options – for being too expensive or too cheap compared to the budget – there would still be over 1,600 different shopping trolleys that Sippel’s subjects had to choose between every time.

The neoclassical definition of requires that, when confronted with this amount of choice, the consumer’s choices are consistent every time. So if you choose trolley number 1355 on one occasion when trolley 563 was also feasible, and on a second occasion you reversed your choice, then according to neoclassical theory, you are ‘irrational’.

To put it bluntly, expecting consistent behavior out of highly variable humans that live in an very complex world is nonsense. Humans are fascinating animals and any theory that tries to put our behavior in a mathematical equation will have severe problems.

Links:

- Not Rational Utility Maximizers by John Aziz

- Behavioral Finance Lecture 01: Debunking Revealed Preference by Steve Keen

References:

1. Keen, Steve. Debunking Economics: The Naked Emperor Dethroned? London: Zed Book, 2011. Print.

2. Sippel, R (1997) ‘An experiment on the pure theory of consumer’s behaviour’, Economic Journal, 107(444): 1431-44